In April 1965, President Lyndon Johnson sat outside the Texas elementary school he attended as child, and, seated next to one of his childhood teachers, signed into law the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), ushering in a new era in the role of the federal government in K-12 education.

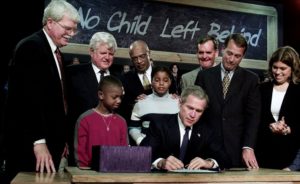

Through a series of provisions—especially Title I—ESEA set out to use federal education funding as a vehicle for equalizing access to quality teaching and materials particularly for students in schools in lower-income communities. At the time of its passage, Congress called for ESEA to be reauthorized every few years. With each reauthorization there came some incremental changes in the amount of federal oversight in K-12 public schools, though the role remained fairly limited because of strong partisan disagreement about federal involvement in public schools (opposition highlighted in the creation of a cabinet-level Education Department under President Jimmy Carter in 1979 and the gutting of that department’s budget a few years later by President Ronald Reagan). But, over the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, a growing chorus of business leaders called for more policy coordination in American public education rather than different standards and expectations by state, using the argument that the wide range of effectiveness among public schools was limiting the effectiveness of the country’s workforce. With that chorus getting louder, one of the first pieces of legislation supported by President George W. Bush in 2001 was the reauthorization of ESEA. Passed June of that year and signed in January 2002 the “No Child Left Behind Act” (NCLB) vastly increased the role of the federal government in K-12 public education by making state access to federal Title program dollars contingent upon:

- Setting specific measurable objectives for students in reading and math, including objectives for students with disabilities, students who qualify for free or reduced price meals, and students with limited English proficiency

- All students reaching 100% proficiency in reading and math within 12 years (by the end of the 2013-14 school year

- Establishing consequences for schools that failed to make “adequate yearly progress” (AYP) for consecutive years

In the years that followed, NCLB had substantial impact on the day-to-day practices and focus of schools, both in ways that were intended and others that were not. While many lauded the act for focusing attention on the core skills of reading and math and also on the outcomes of students considered “educationally disadvantaged”, many others—especially those who taught in schools—lamented the overemphasis on standardized tests and their outcomes, the neglecting of arts, science, history and physical education, and the bureaucratic requirements of the law. After Congress failed to reauthorize ESEA on time, the U.S. Education Department granted many states waivers to the AYP provision of NCLB as the 100% proficiency deadline loomed, and the advent of the Common Core State Standards and the creation of the Race to the Top grant program were pointed to as further consolidation of federal control over education, enough bipartisan frustration led to passage of the “Every Student Succeeds Act” (ESSA) in December 2015.

Under ESSA, it appears as if the pendulum is swinging back towards giving states more control over K-12 education and reducing—but not eliminating—the role of the U.S. Education Department. States are now in the process of making decisions about accountability goals, testing, and other areas. The Georgia Department of Education has several ways parents and teachers can learn more about the state’s ideas in these areas and offer feedback, including in-person feedback sessions like the one happening in Fulton County the evening of September 14. I would strongly encourage you to find some way to learn more and offer your feedback. As the history of ESEA from 1965 to today has shown, policies set at the national or state level can really shape the school experience for students and for teachers in ways both good and maddening. If you care about that, here’s one chance to make your opinion known before those policies are set.